Yesterday, I got to speaking with a fellow I had met a few days before at a friend’s wedding in beautiful Cape Town. We had both just arrived from SA and had the chance to chat while making our way through the arrivals queue. Almost as soon as we started talking the conversation turned to thoughts about our futures. This wasn’t surprising given the events of the past few days.

You see in attendance at this wedding was a cross-section of Nigerian professionals between 30 and 35. Most of us are at about the 10-year mark in our careers and are working for big organisations around the world. Some are recently married—3 or 4 years—some have a thought to get married soon. Some have kids, others are thinking about them. The gatherers had mostly come out of the same secondary schools or had met early in their careers in Lagos, but they had since fanned out across the world. San Francisco, Boston, London, Philadelphia, Geneva, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Abuja, and yes, Lagos, were some of the cities represented there. In short, a reunion of sorts, and a good time to reflect.

What had the past decade taught us? How had our different careers unfolded and could it show us anything about the next ten or twenty years? There are of course many dangers in comparing oneself to anybody else, but there are also lessons, realisations, admissions which can help to clarify what we must do or to dig-up some buried truth which we have been too afraid to confront.

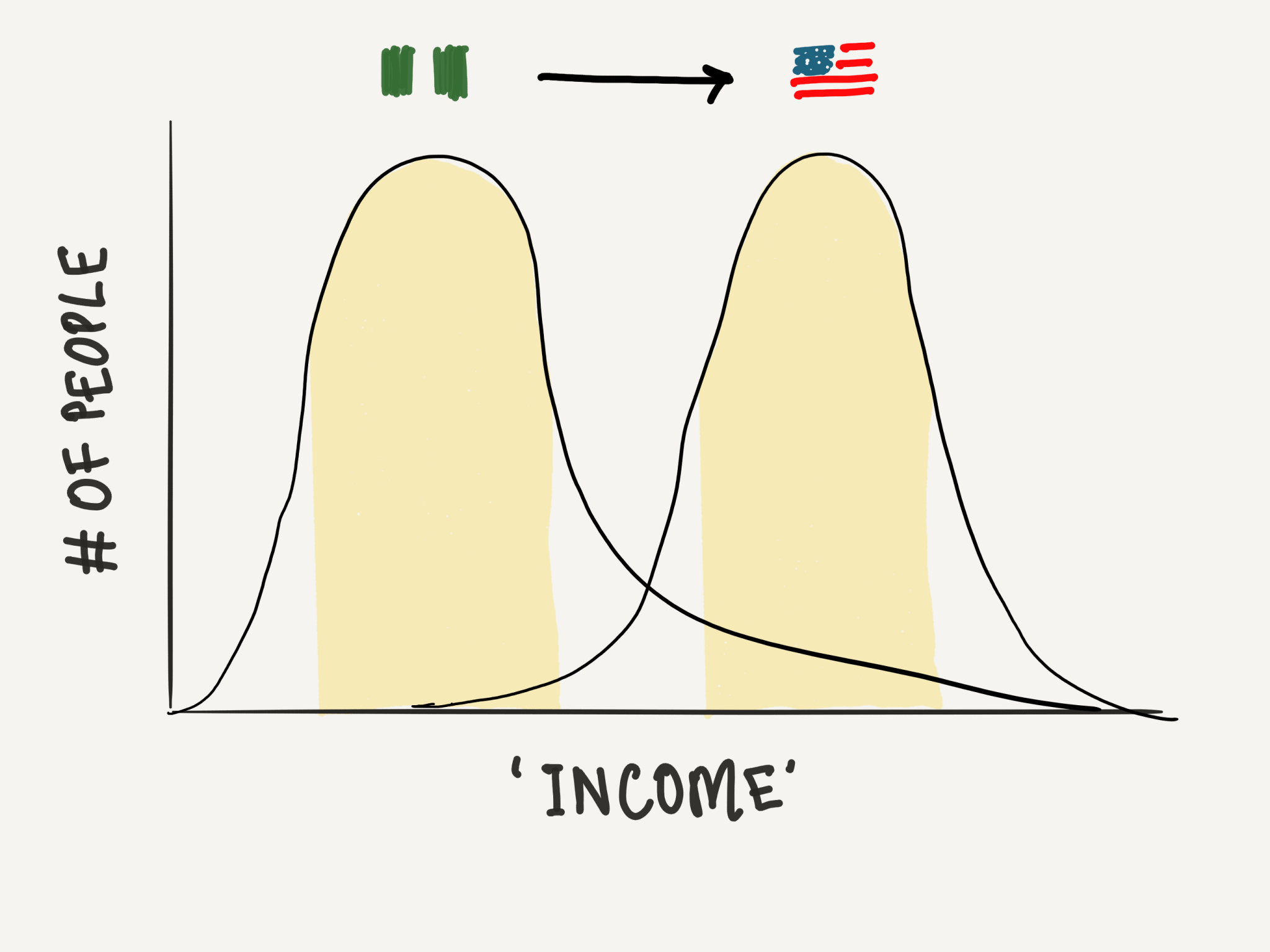

For the folks living outside Nigeria, there was a quality of leisurely confidence in their demeanour. These were young, rich men. They’d seen their incomes rise, through the last 10 years. Predominantly finance types, they had hustled their way into some investment banking, private equity, trading or investment management job in the developed world right after the financial crisis of 2008, and had ridden the wave of increasing market valuations, even as inflation held steady or fell, economies grew, and unemployment rates dropped across the developed world. Young money, really.

For the Nigeria-based folks, the same period has been a bit more challenging. Of course there was the period of the oil boom. After a violent collapse in 2008, between 2009 and 2011 the oil price climbed relentlessly from the 40s to the 100s and remained there through 2014. As if on cue, Nigeria entered a goldilocks period with a relentless stream of good news. The country was awash with oil dollars, the currency was strong, GDP was revalued upwards to $510bn, and Africa was still rising. Most importantly, the middle class felt rich and there was a new swagger about the nation.

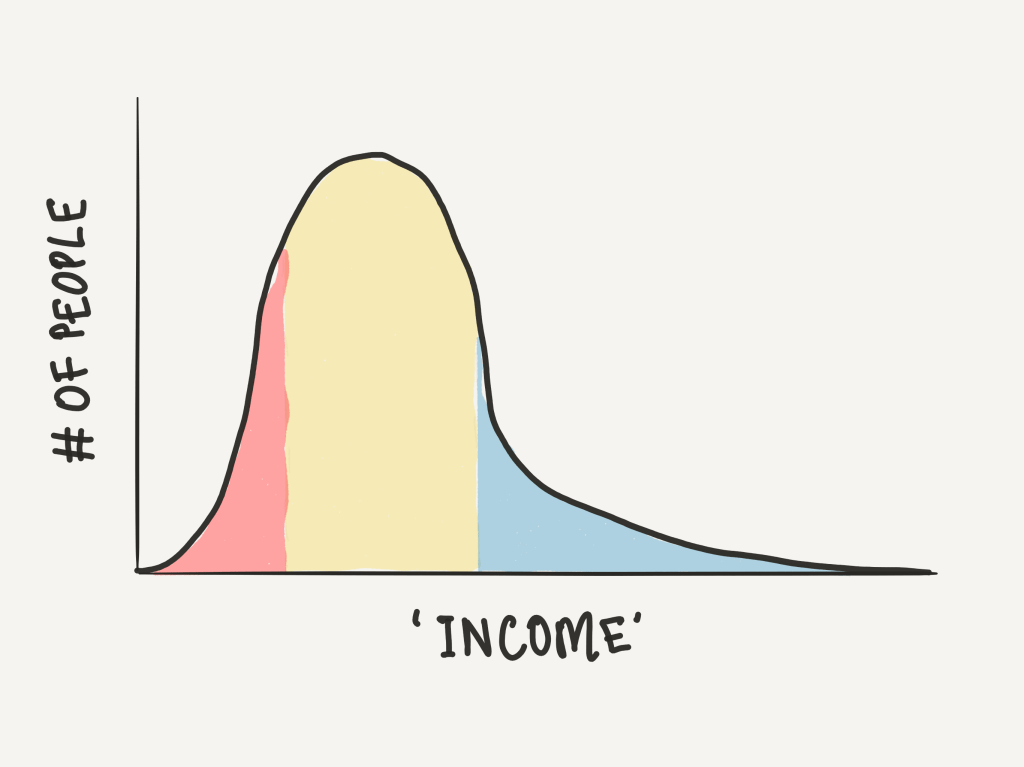

Then the oil market collapsed and the country plunged into a leadership quagmire which metamorphosed into a complete clusterfuck. Incomes which had peaked in dollar terms in the 2011 to 2014 boom years got absolutely crushed in the massive devaluation of 2016. [From the beginning of 2011 to date the naira has more than halved in value against the dollar.] Inflation gathered a head of steam just as the economy was grinding to a halt, attended by a new reality which promised that Nigeria was ‘open for business’ while doing just about everything to ensure it was closed. Whispers of ‘stagflation,’ ‘IMF,’ ‘debt,’ ‘structural adjustment programme’ grew, words which I naively thought we had buried in the 80s. For those in it, it was living through wave after wave of scarcity and dislocation. No petrol, no diesel, no kerosene, no jet fuel, no dollars. Older Nigerians were better prepared, they spoke wearily of the late 80s and early 90s, when careers, lives, and aspirations were destroyed by macroeconomic events which they were oblivious of. It reminded them too much of it. My father described that period as: “Seeing the ground beneath your feet give way.”

No, there was no leisurely confidence in our demeanour. No young money, things are tough. In that airport yesterday, my friend and I were thinking the same thing: Should we stick around? Does it make sense? We are both fathers, should we really keep our kids here? Nothing is academic when you have kids. If your income gets squeezed by inflation or the exchange rate, you feed them less, or they cannot go to school. Nothing about that is theoretical. It is a bit more serious than social media banter or quips about being optimistic or patriotic. When people make shit-headed economic decisions, they are attacking my livelihood and my aspirations, my kids, my loved ones. And this is kind of the bottomline in all this: The ground we stand on is too uncertain. Sure and sturdy one minute, erupting the very next.

Why am I writing this? I don’t know. I guess I’ve got shit on my mind.